What do we have to show for 25 years of social movements and protests?

From 'The Battle of Seattle' to the military invasion of Los Angeles, mass protests have erupted time and again, but to what end?

This is a version of a chapter that I wrote for the 2025 edition of The Socialist Register, an annual book covering left history, strategy, and theory. The editors asked me to focus on the U.S.-based Palestine Solidarity Movement that erupted at the beginning of Israel’s genocide of Gaza in October 2023. To put the movement in context, I start with the 1999 protests in Seattle against the World Trade Organization and then examined other movements such as the Iraq Antiwar Movement, Occupy Wall Street, and Black Lives Matter.

I have reported on every movement, and have been privy to significant conversations and events that have rarely been discussed openly if at all. Writing this allowed me to think deeply about the contemporary arc of left history and how we ended up in this fascist nightmare.

I spent more than a month interviewing dozens of people, poring over hundreds of articles, reviewing my work, and synthesizing it to write a story that I hope is forthright, though hardly complete, of left movements over the last three decades.

Every leftist knows there is an intense reluctance to talk openly about left strategy, decisions made and not made, and failures. This silence has been compounded by the demise of left media. There are few venues left for critical discussions of left movement history and strategy.

That’s why your generous financial support is so important. It gives me the time and space to dig into stories, make connections, and describe the bigger picture. It also allows us to engage in dialogue and think about strategic actions that we can take to rebuild a left that can win.

Please consider making a financial contribution right here on Substack to enable me to do more unique reporting and analysis like this. Whether it’s $10 or $100, any amount is meaningful because it is a sign you support more work like this.

Also, please consider subscribing to Socialist Register. It’s only $25 a year and you get access to hundreds of thoughtful papers on pressing social, political, and economic issues.

Since this is a chapter in a book, it’s obviously long. I’ve posted photos from some of the protests I’ve covered over the last decade. There are half-a-dozen sections, so you can read it in chunks or one go. You will notice many quote marks, but no citations. There are more than 100 footnotes in the SR chapter. I haven’t figured out how to transfer the citations, but once I do I will post a footnoted version. All opinions and errors are mine.

THE CONTEMPORARY HISTORY OF THE US PALESTINE SOLIDARITY MOVEMENT

During the heady days of Occupy Wall Street (OWS) in the fall of 2011, protesters would chant, ‘All day, all week, occupy Wall Street’ while marching around the financial district in Lower Manhattan. In Portland, Oregon, during the summer of 2020, when the George Floyd movement protests raged for more than 100 days in a row, crowds of black-clad gas-masked demonstrators would chant, ‘Stay together, stay tight, we do this every night’. During the spring of 2024, when encampments in solidarity with Gaza spread to about 120 US university and college campuses, students would chant, ‘Disclose, divest, we will not stop, we will not rest’.

These three slogans reveal the nature of US-based left movements in the first quarter of the twenty-first century. Foremost, the slogans indicate an imperative to act. Action is not a tactic. It is the end. The tactic – a public camp, social media-driven protest, nonstop demonstrations – is the organization and creates the revolutionary agent. The tactic is memeable and viral. These movements achieve success by creating an innovative moment in which a protest tactic captures media attention, briefly puts state power on the defensive, and then spreads rapidly. Rarely is there a developed strategy or defined leadership, organization is minimal if any, and protests tend to ossify quickly and veer toward maximalism. The porous, opaque and unstructured nature of these movements leaves them open to cooptation and opportunism. These movements are either outright anarchist, as with OWS, or have significant anarchist elements. But, being voluntarist, ephemeral and in constant flux, they tend to be more anarchic than anarchist. Activists claim decision-making is horizontal and uses consensus, but in practice those with the most cultural and social capital wield the most influence. In other words, they replicate the hidden power structures that Jo Freeman described in her landmark essay ‘The Tyranny of Structurelessness’.

I term these ‘spontaneous protests’, but in a specific manner. After OWS began, social movement historian Frances Fox Piven said that anyone who called the protests spontaneous doesn’t understand them. Piven was correct that there was a history of ideas, individuals and organizations from which Occupy emerged. At the same time, however, movements like Occupy, George Floyd and Palestine solidarity have attracted millions of new participants in short order and with little organizational infrastructure. The theoretical underpinning of these movements is similar to that of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). In the early 1900s, the IWW sought to organize all workers regardless of race, gender, citizenship or work into ‘One Big Union’. The Wobblies lionized regular agitation and ‘striking on the job’. They would fight for concessions but refused to compromise with bosses. Their goal was not to win employment contracts, but rather to grow powerful enough to seize the means of production and operate the economy themselves, democratically and for social ends.

While the Wobblies had little of the allergy to organization and structure endemic to ‘spontaneist’ movements today, they share important similarities. For example, if public space is substituted for the shop floor, then there are clear parallels between the Global Justice Movement (GJM) that emerged in 1999, Occupy Wall Street and the Wobblies. OWS and the GJM refused to compromise with the state, especially police; they sought to unite everyone in protests that would build until they overwhelmed ‘the system’; and then ‘the people’ would employ direct democracy to run society along anti-corporate if not anti-capitalist lines. Instead of strikes, the GJM had ‘convergences’, where everyone would gather to protest capitalist summits such as those of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), World Economic Forum and World Trade Organization (WTO). Occupy camped in prominent public spaces and used general assemblies, where ‘the new world was being built in the shell of the old’ (a riff on a saying attributed to Antonio Gramsci). If the Wobblies were guilty of wishful thinking, many activists today indulge in magical thinking. They lack theory and a vision of the ideal society, instead believing that once capitalism collapses, we will naturally revert to an anarcho-communitarian society where resources and power would be distributed equitably and consensually.

OWS lacked strategy and, famously, even specific demands, but it had an impact. In 2011, when President Barack Obama sought a ‘grand bargain’ with Republicans to reduce the national debt by cutting Social Security and Medicare, Occupy flipped the script from austerity to income and wealth inequality. It popularized discussion of class and class power through its framework of ‘the 1%’ and ‘the 99%’. OWS opened the door to low-wage worker organizing such as the Fight for $15 campaign, and paved the way for Bernie Sanders’ 2016 presidential campaign, which in turn spurred the meteoric growth of the Democratic Socialists of America and helped revive socialism as a political and intellectual force among American youths, who in 2024 were more likely to view it positively than they viewed capitalism.

With the help of Naomi Klein and The Yes Men, I founded The Occupied Wall Street Journal in October 2011, which gave a legacy media spin to a movement sparked by new digital media — for better and for worse.

These movements are part of the context in which the US-based Palestine solidarity movement (PSM) evolved over the last three decades. It developed a network of Palestinian, Muslim and anti-Zionist Jewish groups that took the lead in organizing against the Israeli genocide in Gaza that began in October 2023. Students took centre stage in the spring of 2024, when university crackdowns on campus protest encampments backfired and galvanized public support. The student camps were direct descendants of OWS in that they were continuous protests in public space, employing a disruptive tactic that went viral and thereby influencing national politics. There were important differences as well. Unlike Occupy, the students had demands; there were leaders, even if decision-making was often spur of the moment; many students were involved in Palestine solidarity organizations before they set up camp; and many were wary of the media, as reflected in the discipline they showed in messaging. While the students faced considerable police violence, as the Occupy protesters had, they also had to contend with McCarthyite political and legal repression.

In April 2024, I interviewed dozens of student protesters at New York University, the New School, Fashion Institute of Technology, Columbia University and City College of New York, all of which are in Manhattan. Students demanded transparency in university endowment investments, which are often secretive and can be enormous – $13.6 billion for Columbia and $50.7 billion for Harvard. Students called for universities to divest from companies implicated in the occupation, particularly weapons makers and tech giants like Google, Amazon and Microsoft. They wanted universities to cut joint programs with Israeli universities. They also demanded amnesty for students, faculty and staff subjected to disciplinary procedures for protesting, which at Columbia University was ‘at least 160 students’. Students made decisions by some form of voting, but would defer to Palestinian-Americans and others directly affected by Israeli-US wars, just as African-Americans usually led the George Floyd protests in 2020.

The Palestinian liberation movement is one of the last national liberation and decolonization struggles. The PSM resembles anti-imperialist, antiwar and solidarity movements since the Spanish Civil War, but for the first time since the 1930s the Marxist left is not central to organizing it. The PSM is also similar to the George Floyd movement in that it has raised mass awareness and discredited state violence, even as ruling-class interests and institutions struck back with police violence and political and legal repression. The challenge for the PSM is building power to disrupt US support for Israel – just as the antiwar movement did during the Vietnam War, which combined with Vietnamese resistance and armed struggle to defeat the American war effort. This requires organization, leadership and a mass movement that is broad, strategic, disciplined and refuses to compromise on Palestinian national liberation and ending Zionist settler-colonialism. But it also faces the same trap confronting all movements today. PSM protests are highly dependent on social media and can unleash mass disruptive power seemingly out of nowhere. But social media also determines the form of protests, and in particular the ephemeral viral tactics they adopt, making them almost impossible to organize and institutionalize in the very moment when they have the most influence.

THE FIRST LIVESTREAMED GENOCIDE

Media is inseparable from modern US wars and antiwar organizing. If television made Vietnam a living-room war, then smartphones made Gaza a social-media war. Speaking from the Columbia University encampment in April 2024, Darializa Avila Chevalier, an alum, said, ‘This is a generation that has witnessed a genocide for the last six months on their phones. Witnessing something this horrific has been incredibly formative. They are really committed to movements for social justice. This will never leave them.’

Columbia University students at their encampment against the genocide of Gaza days before the university administration gave the NYPD approval to violently evict the peaceful protest. Student protests briefly put the pro-genocide Biden administration on the defensive, which temporarily paused a shipment of bombs to Israel.

Social media is a double-edged sword. On 25 May 2020, videos went viral of a cop murdering George Floyd, and of a white woman calling 911 to falsely claim she was being threatened by Christian Cooper, a Black man birding in Central Park. They triggered the largest protests in US history, with more than 15 million people demonstrating in 2,400 towns and cities. But the far right found social media useful, too. The Washington Post reported that right-wing militias ‘often coordinated on Facebook’ to threaten protestors. In rural Oregon, ‘of the more than 60 actions … virtually all of them have encountered backlash from armed groups, whether in the form of intimidation on social media or actual boots on the ground’. Social media put millions in the streets, but they outran attempts at coordination. The response to protests against police violence was more police violence, including ‘mass arrests, indiscriminate use of projectiles and chemical weapons (e.g., rubber bullets, tear gas, pepper spray), and driving police vehicles into crowds of protestors’. State violence squashed protests by millions because there was little organization, strategy, leadership or discipline.

A month later, the George Floyd protests had petered out in nearly every city. In Portland, demonstrations had dwindled to a few hundred people per night until Trump sent in a Border Patrol military force. His strategy was to ‘amplify strife in cities’ so as to generate ‘viral online content’ that could be used in his re-election campaign. Trump was borrowing a trick from Portland. A few years earlier, provocateur Andy Ngo had gained notoriety for deceptively editing videos to drive a narrative that antifa hordes were destroying Portland and threatening white residents. Far-right gangs like the Proud Boys and Patriot Prayer would point to the videos to justify invading Portland to attack antifascists, often with the complicity of the Portland police. The gangs would then use video clips of their own violence to build their profile and attract new recruits. In fact, they used Portland as a proving ground to grow their ranks and develop the tactics they employed during the January 6 insurrection in Washington, DC.

On the left, savvy individuals can quickly build a mass social media audience that they can use to shape protests. Even if they are well intentioned, there is a lack of accountability and democratic decision-making, temptations for personal and financial gain, and no mechanism to create lasting institutions, along with pervasive maximalism, call-out culture, burn-out, and burning protesters who are arrested but are not provided with legal, financial, or social support needed to handle the consequences. Organizers can’t ignore social media since it is a primary form of communication and recruitment. But for Palestinians and solidarity groups this comes at the cost of systematic censorship by Instagram and Facebook, owned by Mark Zuckerberg, and X (formerly Twitter), owned by Elon Musk, the two wealthiest men on the planet. Many groups have also been ‘deplatformed’. Before the start of the fall 2024 semester, Instagram erased the Columbia University chapter of Students for Justice in Palestine’s account of 124,000 followers and ‘permanently deleted’ all the information associated with it, erasing years of work. The far right has also become adept at using social media to incite violence against the left. On 30 April 2024, a social-media organized gang of extremists funded by Zionist celebrities assaulted a student encampment at UCLA for five hours – sending 25 people to hospitals with injuries – while police watched.

Despite these obstacles, the students put Washington and Tel Aviv on the defensive. Global support for the students reached Palestinians in Gaza, who wrote messages of gratitude on their tents. At the same time, solidarity activists were unable to meaningfully fracture the US relationship to Israel. Instead, the aggression got worse. One year after the genocide began, Israel invaded Lebanon with US support, repeating the tactics it was using in Gaza: killing thousands, targeting healthcare workers and hospitals, destroying residential areas and civilian infrastructure, and displacing more than a million civilians. Reflecting on organizing against the US-Israeli wars, Rabbi Alissa Wise, founder of Rabbis for Ceasefire and co-author of Solidarity Is the Political Version of Love: Lessons from Jewish Anti-Zionist Organizing, said, ‘I think one of the things that’s really hard right now is that we’ve had a year of sustained protest where we’ve demonstrated mass public grassroots refusal of Israeli genocide. In the US and across the world, we’ve seen the highest level of Palestine solidarity probably ever. And yet there’s nothing to show for it in terms of stopping the genocide.’

At a march in New York City for Black Lives Matter in December 2014. BLM exploded after police murdered unarmed teen Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri that August, sparking protests nationwide. More than a decade later, it’s an open question whether BLM was a real movement given how little organization it created.

ORIGINS OF SPONTANEOUS PROTEST

Spontaneous internet-driven protest goes back to the GJM, when thousands of nonviolent protesters gathered in Seattle to shut down the World Trade Organization Ministerial on 30 November 1999. The protest outside emboldened countries from the Global South on the inside to reject a US-led pact to institute neoliberal trade and finance policies worldwide. The success made ‘summit-hopping’ a fad. Protesters dogged world leaders from city to city – Prague, Quebec City, Washington, DC, Genoa, Miami, Cancun – trying to create enough chaos to prevent them from advancing policies and trade deals that primarily benefit powerful countries and corporations.

The theory of change was to get enough people in the streets, and to shape actions in ‘spokes councils’, which could gum up the gears of power and cause capitalism to grind to a halt. The theory valorized action while eschewing any real politics beyond sloganeering. There was no shared vision of what participants were fighting for, who was the agent of change, or the form of counter-hegemonic power (such as vanguard formations, industrial unionism or political parties). Slogans and buzzwords filled in for politics: ‘horizontalism’, ‘consensus’, and ‘another world is possible’. Months after Seattle, Naomi Klein – who shot to fame after her first book, No Logo, was published days after the failed WTO ministerial and became the movement bible – likened summit hopping to nomadic followers of the Grateful Dead. She warned that mobilizing tens of thousands of people to trek from protest to protest was sucking up all the organizing energy and losing sight of the need to connect globalization to local issues. Additionally, capital had many ways to respond. Trade meetings retreated to fortress resorts in Qatar and Switzerland. Legal repression intensified, as did violence. Police fired more than 5,000 canisters of tear gas in Quebec City and killed a protester in Genoa, Italy.

At the same time, the GJM did achieve results. The opposition it crystallized killed the Doha Round, the WTO’s attempt at a global trade deal. Reverberations continued for years with the collapse of the Free Trade Area of the Americas in 2005 and the Transpacific Partnership in 2017. Also, the protests did succeed on their terms – but no one knew it. In September 2001, nonviolent direct action was planned to shut down the semi-annual IMF and World Bank meetings in Washington, DC. Demonstrations in the spring drew 20,000 activists who blocked streets and intersections, but failed to stop the talks. By the fall, the AFL-CIO signed up to protest. Police estimated 100,000 people would be in the streets. A source in the IMF claimed police warned the agency that they could not guarantee the summit’s protection. The IMF quietly canceled the meeting weeks in advance. But the September 11 attacks saved their hide as organized labour and major NGOs withdrew from protests, leaving only 5,000 hardcore activists who were brushed aside by police.

At heart, the GJM was anarchist. Many activists were influenced by the Zapatista Movement in Chiapas, which launched a 12-day war against the Mexican government on 1 January 1994, the day NAFTA went into effect. The Zapatistas practiced bottom-up and horizontal decision-making. They contrasted themselves to the top-down Marxist-Leninist guerrilla armies that had led many anticolonial revolutions in the 20th century. The Zapatistas lived mainly in peasant communities on the fringes of capitalism. Since they shared social, cultural and economic life, it was possible to make decisions collectively, enforce them and punish those who violated the rules.

The GJM was based on ‘affinity groups’, modeled on the Spanish Civil War. US-based activists often had anarchist credentials such as Earth First!, Ruckus Society, Direct Action Network, the IWW, forest defense, United Students Against Sweatshops, and art and music collectives, alongside members of labour unions, ‘fair trade’ advocates, indigenous people, environmentalists and farmers. Prior relationships enabled some accountability, but nothing like the Zapatistas could impose. However, activists in movements the GJM influenced, such as OWS, formed relationships after joining a camp, meaning there was no meaningful accountability. From there, OWS influenced Black Lives Matter in Ferguson, Missouri in 2014, the Standing Rock oil pipeline blockade in 2016, Occupy ICE in 2018, the George Floyd Movement in 2020 and the student movement for Gaza in 2023–2024. These were spontaneous, digital media protests that captured lightning in a bottle. Standing Rock and the student movement for Gaza both lasted more than a year because there was pre-existing organization and leadership. But the others rarely lasted more than a couple of months, collapsing as numbers dwindled, and activists often flailed about after the glow had faded trying to recapture the magic.

While activists under the age of 30 are usually familiar with Occupy Wall Street, almost none know about the Global Justice Movement despite the fact OWS would never have happened without it. GJM activists played a central role in pre-organizing for OWS and gave it political shape with the General Assembly, horizontalism, and consensus decision-making. The history came full circle when during the George Floyd uprising activists in Seattle took over part of the Capitol Hill neighborhood in June 2020 and declared it the Capitol Hill Organized Protest, or CHOP, which like Occupy camps disintegrated quickly due to internal conflict and deliberate police malfeasance.

Precisely because anarchists lack state-recognized institutions such as nonprofits, they are free of constraints such as the need to follow the dictates of funders, legal restrictions on political activity, institutional fears of state repression, the safety or job security of workers, public image, or the imperative to ensure institutional reproduction. This allows a high degree of creativity and risk-taking, as well as ignominious flame-outs. The initial spark is based on an innovative tactic that reconfigures public space, such as horizontalist direct action in Seattle, encampments in OWS, social media–initiated protests for the George Floyd movement, and campus encampments for Gaza. Once the movement spreads, activists have little control over what happens next. Anarchist-style network organizing is decentralized, which makes them resilient and hard to crush, but innovation fossilizes quickly. The absence of leaders and strategy leads to sclerotic decision-making. Meetings tend to be formalistic, long and spiked with jargon, which creates barriers to those who lack time or academic backgrounds. When social conditions change, the organizing often dissipates. The GJM, for example, was blindsided by the 9/11 attacks. The Direct Action Network was incapable of figuring out how to reorient and voted to dissolve. One wing of the movement in San Francisco reconstituted as ‘Direct Action to Stop the War’ after the US invaded Iraq on 20 March 2003. They disrupted the city for several days and carried out mass actions for ten weeks, but ‘lacking a strategy’, the energy dissipated.

PAST IS PROLOGUE

If anarchists were not up to mobilizing growing discontent with the war on terror, Marxists were. By the time US forces invaded Iraq in March 2003, antiwar groups had proliferated. The Iraq antiwar movement offers important lessons as it was the last mass antiwar, anti-imperialist movement prior to the 2023 Palestine solidarity movement. One significant commonality was that leaders of the Iraq antiwar movement came from Marxist parties. United for Peace and Justice (UFPJ), a coalition of 1,300 organizations, was led by individuals affiliated with the Communist Party USA and the Committees of Correspondence for Democracy and Socialism, which had broken with the former in 1992, but later reconciled with it (some UFPJ leaders had also been in the 1970s-era Line of March). UFPJ represented the peace and social justice left, and organized major protests on the East Coast from 2003 to 2007. UFPJ was rivaled by International ANSWER (Act Now to Stop War and End Racism), initiated by the Workers World Party (WWP) after the 1991 Persian Gulf War. WWP had a Third World nationalist approach that veered into ‘campism’, meaning it claimed repressive states were anti-imperialist solely because they were on Washington’s hit list. The main antiwar group on the West Coast, ANSWER, broke away from WWP in 2004 and its leaders set up the Party for Socialism and Liberation (PSL). The now-defunct International Socialist Organization (ISO) set up the Campus Antiwar Network (CAN) in 2001, which succeeded a student antiwar group it had organized during the first Gulf War. Finally, the Revolutionary Communist Party employed a grab bag of front groups for antiwar organizing like Not In Our Name, the World Can’t Wait, and Refuse and Resist. Starting in 2002, protests attracted huge numbers, such as the historic 15 February 2003 protests that drew half-a-million in New York City and tens of millions more in nearly 800 cities around the world one month before the US invasion. The three main formations and leaders during the Iraq War – UFPJ, ANSWER and CAN – were a reboot of the antiwar movement during the Gulf War.

Theory and organization explain why Marxists have been prominent in antiwar organizing. Marxism is internationalist – it holds that the proletariat exists without national or ethnic distinctions, and as the revolutionary class it is the agent of change. As such, Marxists place a high value on solidarity with those staring down the barrel of Western power, which is reinforced by Lenin’s work, Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism. There are historical elements, too. US power reached its nadir in the 1970s as defeat in Vietnam loomed. Anticolonial movements were sweeping the global South, and Western youth were intoxicated with revolutionary fervour. Because wars of aggression are brutal, costly and dramatic, Marxists view the passion and dissent they stir as opportunities to act on their politics and build power. Marxists also punch above their weight. Having committed cadres and operating by democratic centralism, in theory if not in practice, enables them to react quickly to new developments and deploy disciplined members to do the necessary leg work. After Iraq invaded Kuwait in August 1990, the Workers World Party set up the Coalition to Stop US Intervention in the Middle East within a few weeks. Others on the left who criticized WWP as opportunists for acting quickly and alone later formed the National Campaign for Peace in the Middle East. Many found the WWP unpalatable because of its history of supporting repression by Communist states, back to the 1956 Soviet invasion of Hungary and Czechoslovakia in 1968. But WWP also opposed US sanctions, which it criticized as ‘financial weapons of mass destruction’, while the National Campaign supported these; and the Coalition called for ending the Israeli occupation of Palestine, which the more liberal National Campaign swept under the rug.

The Palestine Solidarity Movement that erupted in October 2023 after Israel launched a genocidal war against Gaza is the first U.S.-based anti-imperialist movement without the Leninist and Trotskyist left playing a central role since before the Spanish Civil War. The PSM has been hobbled by a lack of Palestinian unity, with no central organization to guide the liberation struggle and international solidarity in the way that the African National Congress did against the South African Apartheid state.

A decade later, the same tensions surfaced during the Iraq War. In 2003, UFPJ coordinated actions in 11 cities against Israel’s ‘separation wall’, thus recognizing that the occupation of Palestine was central to Middle East politics. But downplaying the ‘apartheid wall’, as Palestinians called it, was symptomatic of UFPJ’s approach to favouring political expediency over principle. Soft Zionists in UFPJ, such as Tikkun publisher Michael Lerner, who in 2001 scoffed at the idea Israel was racist, calling it ‘one of the most multiethnic societies in the world’. UFPJ leaders argued that trying to keep 1,300 groups on board and focusing on the Iraq War necessitated avoiding divisive issues. However, this meant pushing other groups overboard if they advocated for Palestinian liberation or against the US war on Afghanistan, two ‘controversial’ issues at the time. Many activists felt sacrificing Palestinians for numbers weakened the movement. ISO cadre in the Campus Antiwar Network pushed student chapters to oppose the Israeli occupation of Palestine. The ISO also helped organize the first protest against the Afghanistan War, in Times Square, right after US bombing began on 7 October 2001.

UFPJ’s expediency surfaced in other ways as well. In 2004, it agreed to NYPD demands that a demonstration avoid the Republican National Convention (RNC) at Madison Square Garden and end on a shadeless, isolated highway at the hottest time of summer. A grassroots outcry forced UFPJ to renegotiate, and 500,000 marched past the RNC without a hitch. But the protest itself was fatally flawed. It was billed as an action to ‘Say No to Bush’s War on Iraq’, thus turning a principled movement into a partisan effort. UFPJ let Democratic presidential nominee John Kerry off the hook, even though he wanted to escalate the Iraq War by sending more troops. In focusing on Bush, UFPJ staff said they were seeking to enlist the support of unions like the United Auto Workers (UAW). They claimed if the RNC protest was nonpartisan, adopting a slogan such as ‘No to the war’, they would have mobilized only a hundred thousand protesters. When asked how the strategy worked, the staffers admitted it did not. The UAW never signed on. When voters angered by the botched war gave Democrats control of Congress in 2006, UFPJ rejected pressuring the party to cut funding for the war, summed up as ‘the power of the purse’. In early 2007, a UFPJ leader told a group of activists in New York City, ‘We don’t need the power of the purse. We are not on the outside shaking our fists. We are on the inside, meeting with them [Democrats] every week.’ When activists asked what they should do, the leader said write and call their representatives. In other words, the strategy was to demobilize activists.

Social theorist and historian Stanley Aronowitz argued UFPJ was practicing clientelism. Their clients were protesters, and UFPJ sought to leverage those numbers with Democrats. Not only did ‘accommodationism’ fail, but the antiwar movement had made imperialism a partisan issue, and the movement evaporated after a final big march in January 2007. Barack Obama co-opted antiwar sentiment in his 2008 victory, won the Nobel Peace Prize, and went on to illegally bomb seven countries without any liberal dissent: Libya, Somalia, Iraq, Syria, Afghanistan, Pakistan and Yemen. There is a question of whether it was inevitable that the antiwar groups would collapse around 2007, when US casualties dropped dramatically and the war disappeared from the headlines. UFPJ withered at this time, as did CAN a few years later. The loss of a principled antiwar movement meant there was little organized resistance to Obama’s wars. It also meant the loss of forums to educate new activists on how both parties supported imperialism, while only differing in their tone and tactics of managing empire.

While the 15 February 2003 antiwar march has become renowned for its size and global scope, there was a protest the previous year that, in retrospect, was just as important. In early 2002, the US left was on its back foot. It was unsure how to respond to the ‘war on terror’ in a time of vengeful, ‘either you are with us or against us’ nationalism. Several rallies were planned in Washington, DC, for 19 April 2002, incorporating causes from anti-globalization to antiwar. ANSWER organized the first national protest against the war on terror that day. Weeks before, then-Prime Minister Sharon reinvaded the West Bank, destroying towns and killing scores of Palestinians. The rally shifted focus to the Israeli occupation, and organizing turned out thousands of Palestinian- and Muslim-Americans to protest. At that point it, was the largest pro-Palestine march ever, drawing up to 100,000 people. Speaker after speaker denounced Israel’s occupation and called for a free Palestine. At the rally, on the National Mall, amid a drum circle hundreds strong, young women in hijabs danced next to dreadlocked hippies. It was an enticing glimpse of the possibilities of multiracial and multifaith organizing. But a deep freeze set in. Whether it was coincidence or causation, the Bush administration ramped up repression of Muslim-Americans. The FBI went on to recruit a staggering number of informants in Muslim communities, tens of thousands by one estimate, to infiltrate, surveil and, eventually, manufacture more than 200 terrorism cases. This pushed many Palestinian and Muslim-Americans away from activism.

This history is not an endorsement of WWP, PSL or ANSWER, nor of their approach. Many on the left describe them as authoritarian, sectarian, manipulative and Stalinist. But their influence cannot be wished away. When movement leaders avoid hard issues like Palestine, the issue doesn’t disappear. Opportunistic elements hammer those who fail to live up to their ideals. The conflict ends up creating divisions that are messier and more toxic than if the issue had been dealt with in a principled manner in the first place.

All this is shaped the context in which the Palestine solidarity movement emerged in 2023. While there is little direct organizational continuity between the two movements, electoral politics has bedeviled PSM organizing just as it did the Iraq antiwar movement.

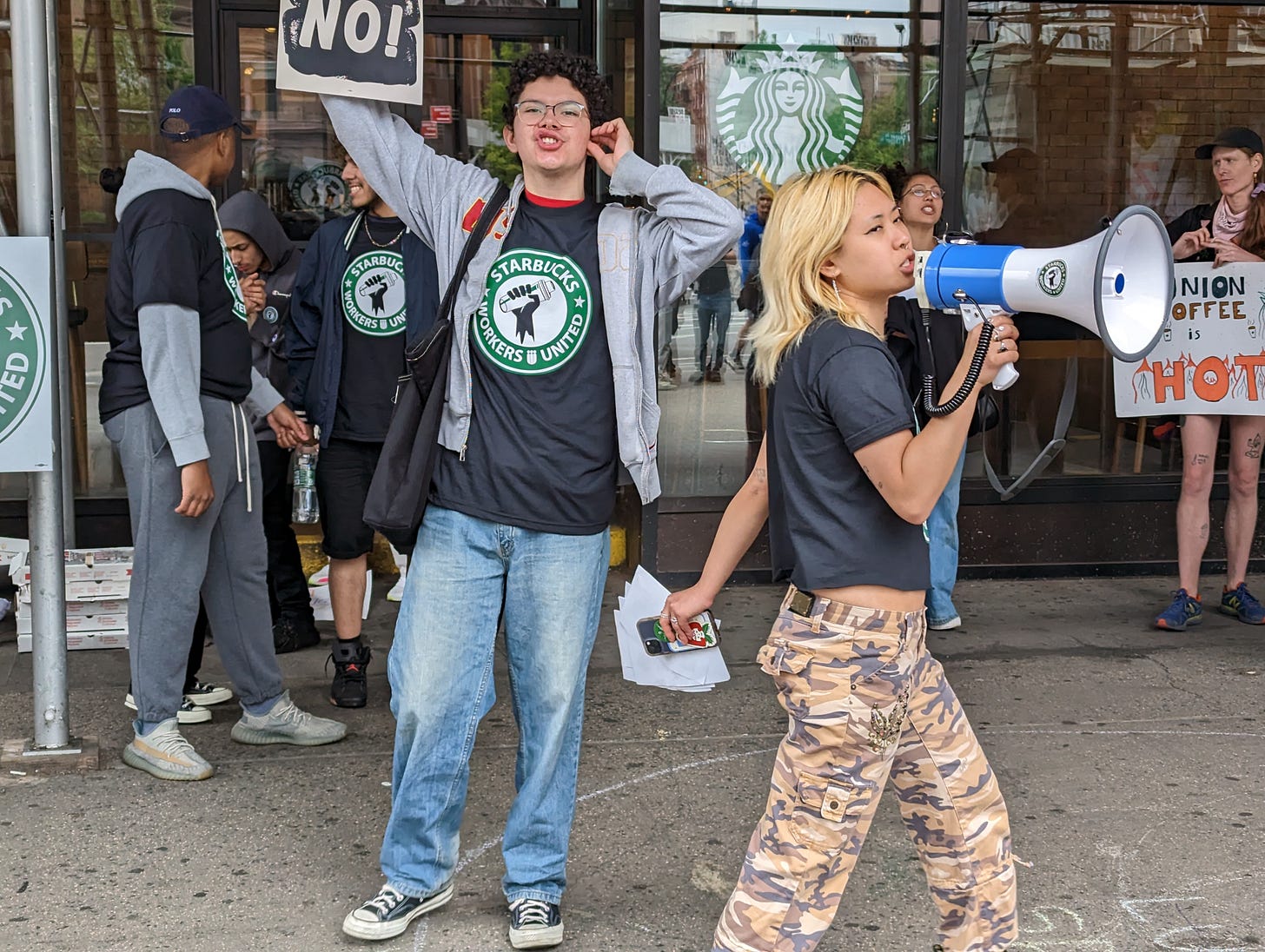

Independent labor unions, such as Starbucks Workers United members here in New York City’s Astor Place, is also influenced by Occupied Wall Street. It inspired Bernie Sanders’ electrifying presidential campaigns that saw the self-styled socialist nearly win the 2016 and 2020 Democratic Party primaries. Sanders legitimized socialism and organized labor among a new generation to the point that 70 percent of the public now supports unions — more than any point since 1965. Independent unions such as SWU, which has won unionization campaigns at more than 550 U.S.-based Starbucks outlets, also owes thanks to Occupy’s rejection of the hidebound left, such as big labor unions that claimed for decades it wasn’t possible to organize retail or food workers.

OCCUPY WALL STREET

The student movement for Gaza is indebted to OWS having modeled the campus encampments on it. One student at Columbia University said of Occupy, ‘we are in awe of you guys’. Occupy was part of a global outburst of protests from 2010 to 2020, as Vincent Bevins details in If We Burn: The Mass Protest Decade and the Missing Revolution. Occupy was a mass uprising, with more than 300 encampments around the country and thousands of groups in towns and cities, and it went global. Frances Fox Piven told me in early 2012 that ‘Occupy Wall Street is the beginning, I think, of a great movement. One of a series of movements that has episodically changed history.’ OWS, Black Lives Matter and the George Floyd Movement all influenced US-based Palestine organizing. Ryna Workman, who as a third-year student at the NYU School of Law participated in its pro-Palestine movement, says, ‘a lot of people were radicalized by the George Floyd movement’. Lara Deeb, professor of anthropology at Claremont Colleges, says that climate justice provided a path for many activists to join the PSM: ‘Students make connections between environmental justice around the world including with Palestine.’ Palestine solidarity also ‘dovetailed with the abolition movement over detention and incarceration’.

The Occupy movement built on GJM-style protests that are spontaneous, emotional, reactive and facilitated by digital media. OWS was a reaction to dull and futile traditional protests. If all protests are theater, then the Iraq antiwar movement was boring theater. It was scripted with protesters passively listening to the same speeches, holding the same signs and reciting the same chants. Occupy was exciting theater – dynamic, chaotic, disruptive and an open-air social experiment. The student movement for Gaza was likewise dramatic and exciting. OWS grew out of the Arab Spring – popular revolts in Tunisia in late 2010 followed by Egypt in early 2011 that ousted dictatorial regimes. They were followed by the ‘Wisconsin Uprising’, protests against an anti-union governor imposing austerity, as well as anti-austerity movements in Spain, known as the ‘indignados’, and Greece that took over public squares in the spring of 2011. In the United States, there were multiple calls for an occupation in the Wall Street area, and a few attempts, before dozens of protesters set up the first Occupy camp in Zuccotti Park in New York City on 17 September 2011. Two weeks later police kettled and arrested more than 700 peaceful protesters marching across the Brooklyn Bridge. Viral video of the arrests inspired hundreds of Occupy camps across the country and around the world. The free-wheeling spontaneity and popular enthusiasm created the kind of moments that grizzled Marxists dream about. Occupy Oakland pulled off a one-day general strike that shut down much of the city and its bustling port. In New York City, about a month after the camp began, mass resistance thwarted plutocrat mayor Michael Bloomberg’s first attempt to evict the camp by sending in the NYPD, which he boasted was ‘the seventh biggest army in the world’.

The Climate Justice Movement is just one recent struggle indebted to Occupy Wall Street, which revived direct action, eye-catching protests, and fingered oligarchs as the group destroying society, political institutions, and the planet. In the Pacific Northwest, “kayaktivism” became a popular tactic to impede ships engaged in oil and gas drilling in the fragile Arctic ecosystem. In Portland, Oregon, in the summer of 2015, dozens of protesters used small watercraft to block one such ship for a few days.

The anarchic elements that birthed OWS doomed it as well. In many cities, the biggest protest was the day the camp was set up. From there, movements dwindled. Maintaining camps was the end. Many became social-service sites, feeding and housing homeless who flocked to safe spaces, as in Detroit or Austin. A few, like San Francisco, became open-air drug dens or were beset by low-level violence, as in New Orleans. By mid-November, Occupy camps in Oakland and New York had been violently ejected. In other cities, activists were paralyzed. They waited weeks or months for the inevitable police sweep with no strategy to build on the organizing. Notable campaigns did emerge, such as ‘Occupy Our Homes’, which fought home foreclosures, labour organizing efforts with bakery workers and locked-out Teamsters at Sotheby’s in New York City, and the groundbreaking Debt Collective that made student debt a national issue and won limited relief under President Joe Biden.

But attempts to shift course, such as ‘Occu-Evolve’, attracted few activists. Instead, activists attempted for a year to create new camps that were crushed by massive deployments of police, who weren’t going to be caught flat-footed twice. In New York City, post-occupation meetings that drew hundreds were drained of energy and numbers by a few people with socialization issues. The problem was that the consensus, horizonalist model had become a pathology. Trying to include everyone no matter how disruptive chased away 99 per cent of supporters. By 2012, days of actions against NATO and corporations that fund the American Legislative Exchange Council, and a May Day general strike, were similar to GJM convergences, but too small and diffuse to have any impact. Meanwhile, liberal outfits like MoveOn, Van Jones’ ‘Rebuild the Dream’ and the Service Employees International Union co-opted the ideas and language of Occupy to boost Obama’s 2012 re-election bid. In October 2012, after Superstorm Sandy thrashed the Northeast, OWS activists created Occupy Sandy to provide vital emergency relief in the first days, as the state was slow to respond. Activists said it was ‘mutual aid’, not charity. The efforts went on for months with little protest and no strategy, with activists filling the role of relief services like the Red Cross and renovating private property for free. It was charity.

FREE PALESTINE

Palestine solidarity in the US goes back to the 1960s, according to Lara Deeb and Jessica Winegar, professor of anthropology at Northwestern University. They write that it originated with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and Students for a Democratic Society in the 1960s, which ‘galvanized anti-racist and anti-war student organizing in the US and included support for Palestinians’. Palestinian-American scholars such as Edward Said, Walid Khalidi and Ibrahim Abu-Lughod put ‘“the Palestinian narrative before college campuses” and broader audiences’. During its lightning war against Arab states in 1967, Israel illegally occupied the West Bank, Gaza, East Jerusalem and the Golan Heights, and solidified US support and backing from Jewish communities in the West. But the 1967 war also ‘consolidated the alliance between Black radical internationalism (and its understanding of a global anticolonial struggle against racial capitalism) with Palestinian liberation movements’, write Deeb and Winegar. By the 1980s, the anti-apartheid movement boosted support for Palestinians, given parallels between South African and Israeli colonialism. In 1987, the eruption of the First Intifada garnered global solidarity for Palestinian resistance, overwhelmingly nonviolent for the first few years.

Huwaida Arraf argues that the lack of unified Palestinian leadership like the African National Congress hurt organizing: ‘I’ve thought if only we had a political leadership that was respected and legitimate in the eyes of the Palestinian people things would be a lot different. The movement is saying one thing and the Palestinian official representatives are saying another.’ Arraf, a Palestinian-American human rights attorney and co-founder of the International Solidarity Movement, which recruits activists to support and document nonviolent resistance to Israeli colonization in the West Bank, says the 1993 Oslo Peace Accord was ‘a very devastating time’. Edward Said called the accords ‘an instrument of Palestinian surrender’, which established the Palestinian Authority as ‘Israel’s enforcer’. Arraf notes that the Oslo Accords ‘broke down a lot of the community structures. It saw the PA usurp the right to represent the people. For Palestinians in the diaspora, I don’t think anyone feels represented by the Palestinian Liberation Organization.’

When the Second Intifada began in September 2000, Israel fired ‘1,300,000 bullets … during the first few days’, wounding and killing thousands and foreclosing the possibility of nonviolence. PLO factions responded with armed attacks, and Hamas and Islamic Jihad with suicide bombers, which, after 9/11, tarnished the Palestine struggle internationally. Alissa Wise told me that, ‘The Palestine solidarity movement faces repression much more than other movements. A lot of Palestinian-led groups took a big hit from the US government targeting those communities in the eighties and nineties’. She says repression after 9/11 and Islamophobia ‘by design had a chilling effect.’

Nonetheless, past organizing laid the groundwork for 2023. Wise, who co-led Jewish Voice for Peace (JVP) in the 2010s, says while the ‘Palestine solidarity movement is amorphous, it has grown tremendously’ since the 1990s. Students for Justice in Palestine, founded in 1993, and JVP, started in 1996, have been in the forefront in organizing against the Israel genocide, especially on campuses. Other leading groups include the Palestinian Youth Movement and American Muslims for Palestine. There is also Al-Shabaka, the Palestinian Policy Network, the US Campaign for Palestinian Rights, the US Palestinian Community Network and Jewish-led organizations such as If Not Now and Jews for Racial and Economic Justice. Wise says veteran antiwar groups active in the movement include the American Friends Service Committee and Fellowship of Reconciliation.

Arraf contends that ‘Students for Justice in Palestine has been transformative, it’s a critical part of the movement. That’s because students and universities are usually at the forefront of social change.’ She says the Palestinian Youth Movement, founded in 2008, is spurred by ‘youth picking up the mantle and not waiting for anyone to pass it on to them and carve out their own space. PYM has been particularly good with taking on our own struggle with deep history and context and not just slogans, and building solidarity with other groups.’ Many activists point to JVP as essential. Wise explains, in Solidarity Is the Political Version of Love, that JVP made ‘crucial political decisions’ in the 2010s, ‘including to move further left by endorsing the Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions (BDS) movement and becoming officially anti-Zionist, even as JVP grew larger and more powerful.’ One JVP member said, ‘The mere existence of a group of a hundred thousand Jews who are explicitly anti-Zionist is a huge breakthrough. It challenges the idea that Zionism is the national aspirations of the Jewish people.’ Arraf adds with regards to If Not Now that because it ‘is not fully anti-Zionist’, it serves as ‘an important bridge between Zionists and the JVP’.

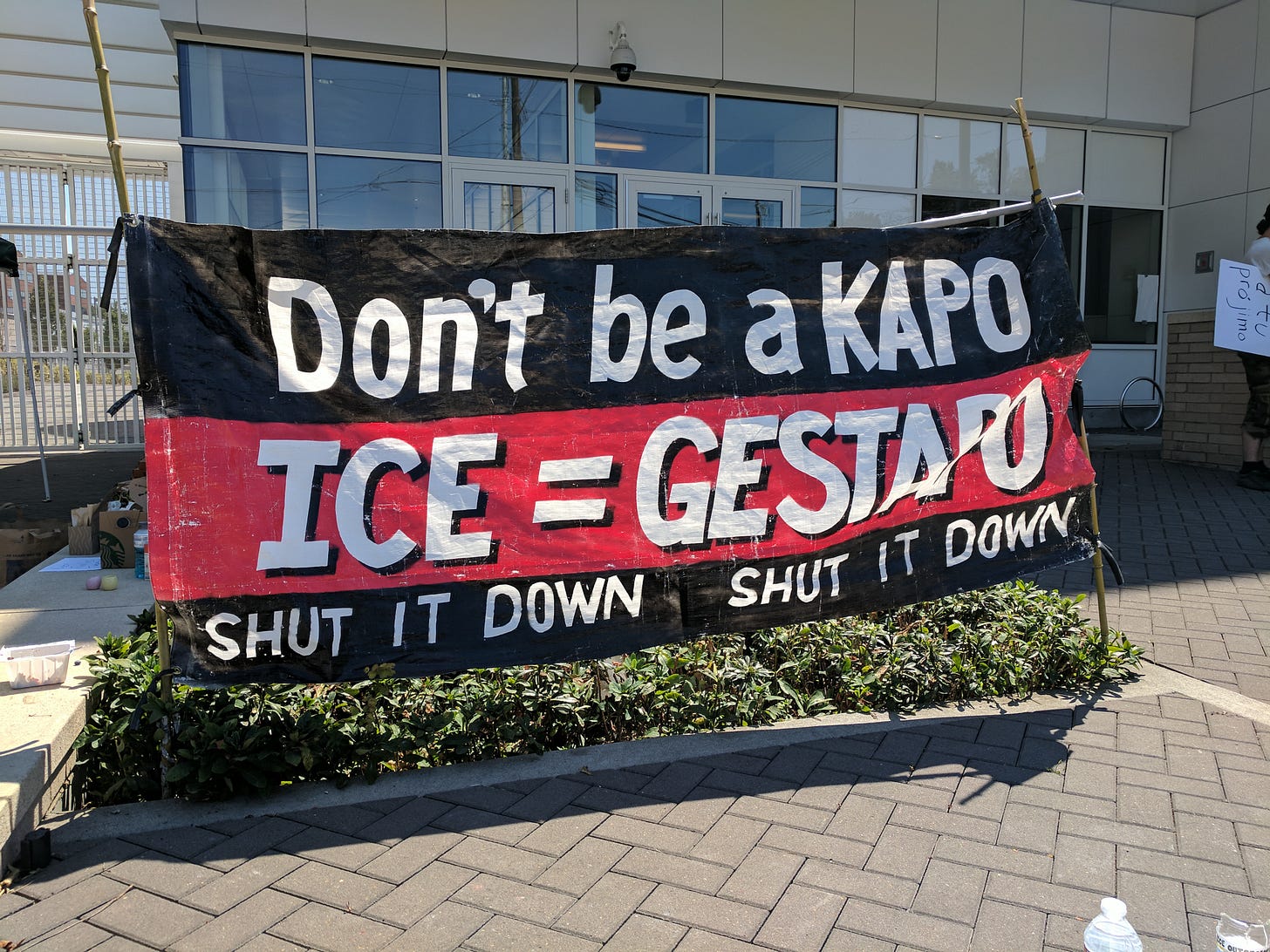

In June 2018, the closure of an ICE detention facility in Portland, Oregon sparked a modest Occupy ICE movement that summer modeled almost directly on Occupy Wall Street encampments. While more focused than OWS in having a specific target, Occupy ICE followed the trajectory of OWS. Trying to manage a camp for weeks in the face of police violence, maximalism, internal strife, and supporting a pop-up community that ranged from immigrant activists to drifters led it to collapse internally.

In 2005, Palestinian civil society issued a call for ‘boycott, divestments, and sanctions against Israel until it complies with international law and universal principles of human rights’. Wise says that the BDS movement ‘has been a real focal point for global solidarity’. The prior year the Palestinian Campaign for the Academic and Cultural Boycott of Israel was initiated, and British educators were among the first to push their universities to cut ties with Israel. Then in 2011, Pink Floyd co-founder Roger Waters shined a spotlight on the BDS campaign by backing a cultural boycott of Israel. In 2014, the one million-member Presbyterian Church (USA) became the first major church to divest from companies profiting off the Israeli occupation, and has since denounced Christian Zionism, declared Israel an apartheid state, and, in July 2024, voted to divest from Israeli bonds. At the same time, there has been a concerted attack on BDS, with 27 US states passing anti-BDS laws by 2019 that penalize companies that cut ties with companies doing business with Israel – even in illegal West Bank settlements. Lara Deeb says the backlash is a sign of the effectiveness of BDS: ‘The amount of money spent by the US and Israeli state to try to thwart boycotts wouldn’t be happening if boycott wasn’t considered a threat.’

It turns out, then, that the spontaneous outburst of the PSM in October 2023 was not entirely spontaneous. In the month after the genocide began, probably more than a million Americans protested in streets and on campuses, as did millions more around the world. Deeb says groups that have facilitated the growing movement include JVP, If Not Now and Open Hillel, the latter an alternative to pro-Zionist Hillel houses on college campuses. She comments:

There are anti-Zionist groups on and off campus that are creating space for Jewish students to ask and think about where they stand on issues without having to abandon their faith and where they can still be in community. Anti-Zionist Jewish students have been in the lead and that has been a crucial change. You have students who have been questioning the Israeli narrative they grew up with. They’re saying, ‘We don’t want these crimes of genocide and apartheid committed in our name’.

Since October 2023, ‘there have been three or four big mobilizations in DC’, says Arraf, which ‘took a lot of people working together’. The Free Palestine March in Washington, DC, on 4 November 2023, drew more than 100,000 people. Arraf says that in the last 20 years, ‘One of the most important developments is groups are working together a lot more. If there is a big mobilization in DC there will now be hundreds of co-sponsoring organizations.’ For its part, JVP has non-violently shut down Grand Central Station, occupied the rotunda on Capitol Hill and blocked the New York Stock Exchange. Despite these successes, Wise says the movement is battling an array of powerful forces: ‘Jewish communal support for Israel is one of the main pillars, but it’s not the only one and ending it will not topple it. There is also Christian nationalism, Christian Zionism, the military-industrial complex, and Islamophobia.’ The corporate media is another pillar, which repeats Israeli propaganda with minimal qualifications.

STUDENTS IN THE LEAD

College students were quick to protest the unfolding genocide and bore the brunt of legal and extralegal repression. As soon as the Palestine movement at Columbia emerged, it was attacked. In October 2023, ‘doxxing trucks’ circled Columbia and Harvard, displaying electronic images of students with their names. Accuracy in Media, which peddles disinformation, dispatched the trucks and published websites labeled ‘Columbia Hates Jews’, naming dozens of students. Many were inundated with online harassment and death threats. One student said Columbia amplified the hostility as it ‘suppressed and harassed students who voiced their support for the Palestinian people’. On 10 November 2023, Columbia suspended the SJP and JVP chapters on thin grounds. Students kept protesting, and Columbia kept punishing them. In January 2024, students at a divestment rally alleged two individuals sprayed them with a chemical while calling them ‘Jew killers’ and ‘self-hating Jews’. Palestinian students claimed the chemical was ‘Skunk’, a weapon used by Israeli forces that smells like sewage and rotting flesh. The university chastised the students for holding an ‘unsanctioned’ rally. On 3 April 2024, Columbia suspended four students and evicted them from housing for holding a webinar entitled ‘Resistance 101’ with a Palestinian activist whom Zionists accused of being affiliated with a US-designated terrorist organization, which the speaker denied.

The spark for the student camps began when the University of Southern California canceled the commencement speech of student valedictorian Asna Tabassum over ‘safety’ concerns on 15 April 2024. The real reason for the cancellation seems to be that she was smeared as antisemitic for being pro-Palestine. Two days later, Columbia University President and Baroness Minouche Shafik testified at Congressional hearings on antisemitism. Before the hearing, 23 Jewish faculty at Columbia and Barnard warned that she would be joining in the ‘political theater of a new McCarthyism’ seeking to destroy intellectual inquiry. Hours before the hearing, Columbia students erected a Gaza Solidarity Encampment on campus. Once back on campus, Shafik authorized a ‘notoriously violent’ NYPD force on 18 April to arrest more than 100 students. Perhaps Shafik thought she had put a lid on the simmering anger. It blew up in her face.

Columbia students revived the camp within 24 hours. That day, senior Sebastian Gomez joined the camp. He said it was ‘a beautiful place with students from every walk of life supporting each other. We have seminars, teach-ins, and I am learning about so many things. People are bringing us wonderful food every day. I’ve eaten better than I have in months.’ Students countered the media drama of ‘administration vs. protesters’ by highlighting the role academia plays in genocide. They created a chart that listed wealthy trustees at Columbia who oversee a $13.6 billion endowment fund that invests in ‘war profiteers’, such as Lockheed Martin and Google. Students said at least five trustees are tied to military contractors, the NYPD and Zionist organizations that ‘manufacture consent’ for Israel. For the students, Shafik was a hatchet-man ‘intimidating’ faculty and staff, calling in the NYPD to ‘punish’ students and doing the bidding of far-right politicians.

Some universities didn’t wait to send in police. On 22 April, in front of the NYU Stern School of Business, the NYPD arrested more than 130 people, including students and faculty, at a protest camp just hours old. On 30 April, walls of riot police blocked off Columbia and City College of New York while hundreds of cops swept in using pepper spray to arrest 282 people at the campuses. On 1 May, New York City’s Mayor Eric Adams exposed the web tying together Israel, academia and policing. At a press conference, Adams said, ‘I really want to thank’ Rebecca Weiner, the NYPD deputy commissioner of intelligence and counterterrorism, for ‘monitoring the situation’. Weiner, who teaches at Columbia’s School of International and Public Affairs, accused Columbia students of the ‘normalization and mainstreaming of rhetoric associated with terrorism that has now become pretty common on college campuses’.

Like Occupy Wall Street, repression often triggered more protest. After being ejected from Stern, NYU students resettled two blocks away for a week before the police raided the new camp. At the New School, after police squashed a student protest on 5th Avenue, teachers initiated the first faculty-led encampment on 8 May. At MIT, students tore down fencing to retake their camp despite threats of suspension. At Harvard University, the suspension of a student group spurred a takeover of the historic Harvard Yard. Students at the University of Texas at Austin kept protesting after police attacked a peaceful gathering with chemical spray, beatings and stun grenades that can maim and kill. By 6 May, Wikipedia tallied pro-Palestine protests and camps at almost 140 universities in 45 of 50 states, and in 29 countries from Argentina to Yemen.

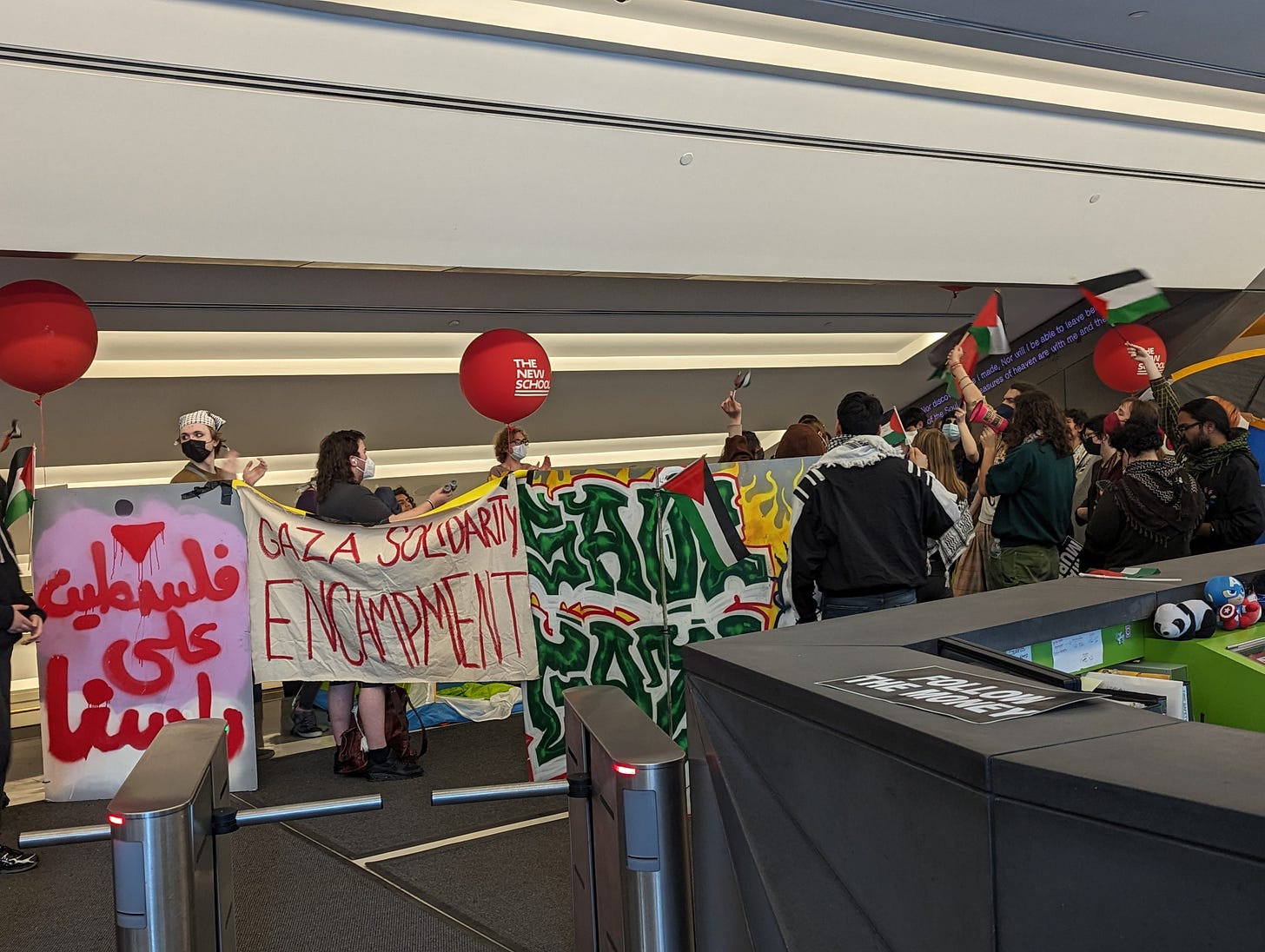

In April 2024, students at the New School University in Lower Manhattan were one of the few campus groups to protest regularly inside a university building. The New School was founded by Jewish intellectuals fleeing European fascism in the 1930s, which might explain why the administration was not as quick to call in the NYPD as Columbia or New York University did. But students were ousted by police not long after the Columbia occupation was crushed.

Violence was not inevitable. At least six university administrations agreed to some demands of students without going from zero to police batons in an instant. The president of Wesleyan University wrote in The New Republic why he declined to send in police. Students at Rutgers University dismantled their camp after the administration agreed to 8 of their 10 demands, although not divesting from Israel or canceling plans to open a branch of Tel Aviv University in New Jersey. In Philadelphia, progressive district attorney Larry Krasner helped keep police at bay from the University of Pennsylvania for more than two weeks. Visiting the camp on 3 May Krasner said, ‘we don’t have to do stupid like they did at Columbia’.

Over the summer of 2024 university administrators introduced new codes covering more than 100 campuses that ‘impose severe limits on speech and assembly that discourage or shut down freedom of expression’, according to the American Association of University Professors. As the fall 2024 semester began, administrators turned the screws to some pushback. NYU designated Zionism, a political ideology, as a protected category like Black people or women. At Harvard University, at least 12 students were suspended for two weeks from a library after holding a silent ‘study-in’ there while wearing keffiyehs and with signs on their computers reading, ‘imagine it happened here’. Following the students’ suspension for violating ‘guidelines on free expression’, 25 Harvard faculty upped the ante by holding their own silent study-in at the same library. They, too, were suspended but that was met with four more library protests, including one where faculty displayed blank papers in reference to Hong Kong activists in 2020 who waved blank sheets of paper in defiance of laws criminalizing speech. At Rutgers University, students wearing keffiyehs were blocked from a library and threatened with arrest. Cornell University suspended Momodou Taal, a British-Gambian PhD student, for participating in a protest, which would have resulted in his immediate deportation. After a spirited defense campaign, Cornell retreated, allowing Taal to continue his program but barring him from campus and teaching duties. Deeb says, ‘The effect of those policies, the lingering effect of arrests, the limiting of academic freedom has created a chilling effect on campuses for many people as it is intended to do.’

In August 2024, protests took place for five days straight at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago. The largest march drew about 4,000 people, mainly from ‘Little Palestine’, the largest Palestinian-American enclave in the country. The DNC protests were less than 1 per cent of the turnout at the 2004 RNC protests, despite one poll in June 2024 that showed 64 per cent of respondents backed a complete ceasefire, while only 26 per cent opposed it. In a CBS News poll the same month, 61 per cent supported stopping US arms shipments to Israel.

By the time of the DNC protests, the Palestine solidarity movement had run into the buzzsaw of electoral politics. A campaign to cast ‘uncommitted’ ballots in the Democratic primary instead of voting for Joe Biden gained more than 700,000 votes and sent 30 delegates to the DNC in protest of the genocide. After being repeatedly sidelined by the Harris campaign, the Uncommitted National Movement conducted a sit-in outside the convention hall demanding a Palestinian-American speak at the convention. But Harris’s campaign nixed a long list of speakers, including Ahmed Fouad Alkhatib, who is a member of the pro-Israel Atlantic Council and says he is ‘anti-Hamas’. Alkhatib says he was rejected despite offering to bring along the family of an Israeli hostage and ‘share a message of healing and unity… and confronting hate and extremism’.

During the 2024 Democratic National Convention in Chicago, thousands of Palestinian-Americans protested “Genocide Joe” and “Holocaust Harris.” The largest turnout during the five days, was 5,000 people at most. The DNC was a missed opportunity for the left, which 20 years earlier mobilized 500,000 people to protest the Iraq War at the Republican National Convention in New York City. In 2024, many leftists thought by downplaying the Democrats’ central role in genocide, they could defeat fascism. But many voices warned that the Democrats were alienating so many supporters, it would pave the way for fascism. A stronger presence at the DNC could have forced Harris to commit to ending the genocide then and there. Harris did capitulate in the end, saying she would end the war. But she waited two days before the election, and it was too late. The left’s cravenness helped give us the worst of both worlds: genocide and fascism.

I am writing two weeks after Trump won a race defined by high inflation. Facing headwinds of rising grocery and energy bills, Harris flubbed the contest with the ‘Fyre Festival of Campaigns’: heavy on billionaire celebrities, backed by neocons like Dick Cheney, and bearing a ‘Wall Street-approved economic pitch’. Nonetheless, Gaza was a significant factor in Harris’s loss, as she spent months antagonizing Palestinian, Lebanese and Muslim voters. She closed ranks with Israel’s rampage by repeatedly declaring her support for ‘Israel’s right to defend itself.’ She implied protesting genocide was worse than committing it by telling demonstrators denouncing her embrace of Israel, ‘You know what? If you want Donald Trump to win, then say that. Otherwise, I’m speaking.’ She dispatched Bill Clinton to Michigan, where he outraged voters by claiming Palestinians ‘force [Israel] to kill civilians’. Muslim and Arab voters refused to bend, and it was Harris who capitulated. Two days before the election, Harris vowed to ‘do everything in my power to end the war in Gaza’. It was a victory for the Palestine Solidarity Movement, but the last-minute flip-flop reeked of desperation. Returns showed a staggering drop in the Muslim vote for Democrats, as much as 50 points from 2020 to 2024. That alone cost Harris Michigan. She was also abandoned by young voters, who were most active in Gaza protests. ‘Big liberal college counties’ trailed the ‘Democratic ticket by a point or two.’ Those three factors could have cost her Wisconsin, given Trump won by less than 30,000 votes.

Genocide is like global warming and the Covid-19 pandemic: they all spread unless aggressive measures are taken to stop them. After a year of genocide, Israeli forces began liquidating North Gaza, massacring and ethnically cleansing the 400,000 remaining residents. It was at the same time ethnically cleansing in the West Bank, as part of a killing spree and unprecedented land grab. It extended its genocidal war to Lebanon, with indiscriminate bombing that killed thousands and a land invasion. It was bombing Yemen, Syria and Iran. Even the corporate media, which had claimed for a year that Biden was working hard for a ceasefire, no longer seemed to believe its own lies.

The trends shaping politics and protest that emerged in Seattle 25 years earlier had become more pronounced since then. Digital media delivered a new unimaginable horror every day, from hospitalized patients burning to death in beds from an Israeli air strike, to prisoners being gangraped by Israeli soldiers, to parents carrying dismembered toddlers in plastic bags. These images pushed Palestinian voters, Muslim voters, young voters and left voters away from Harris. Israel’s wars played into Trump’s strongman appeal. He presented himself as a peace candidate who would end the wars and chaos in the Middle East and Ukraine wrought by the Democrats.

A second trend was the disintegration of the Marxist left. Its demise left few spaces to educate and train new activists in the fundamentals of organizing and the history of the left. Social media replaced solidarity, stoking grandstanding, circular arguments and undermining rather than building collective analysis and power. Solidarity means seeing the world through the eyes of the people you support and putting the needs of oppressed peoples before our own. Leftists might protest for Palestine, but fewer and fewer were in solidarity with them. Huwaida Arraf explained the election from a Palestinian perspective:

We are in a very shitty place. You know Trump is horrible and will not be good for you, and may be worse, so you definitely don’t want Trump. But at the same time Palestinians and a lot of other people are done with accepting crumbs from the Democratic Party … It is dangerous to give your vote to a party that is not only actively involved in the commission of genocide but that is gaslighting and dehumanizing Palestinians and Palestinian-Americans, and shunning us, our needs, and our humanity at every turn. It is also belittling our community by thinking that they don’t have to do anything except scare us into believing that the other guy will be much worse. They are literally making us watch our families get slaughtered, paid for with our own money. If you, in the end, turn around and give your vote to the party that has done and continues to do this, then what can’t they do to you and you’ll still vote for them?

Rather than working to end the genocide, which would have improved the Democrats’ chances of winning, many leftists muted criticism and got the worst of both worlds: Trump and genocide. They claimed Trump would be worse for Palestine, meaning they were more opposed to a hypothetical genocide than an actual genocide. They baselessly claimed Harris would end the genocide if elected. Left supporters for Harris vowed, ‘we will hold her accountable when she is in office’. History does not bear this out. Liberals or the left never held Biden, Obama or Clinton accountable. That was done by spontaneous movements with few prior ties to left organizing (other than the GJM).

Most egregious, voting for Harris without making demands was a negation of power. The most power over a candidate is before an election, not after it. A concerted effort might have turned out 50,000 protesters at the DNC, given protests at past conventions and the number of people who had been marching for Gaza. That could have forced Democrats to end the genocide. An uncommitted vote two or three times higher might also have had the same result. Long-time organizers bemoaned the lack of an organizing umbrella like UFPJ, or Marxist groups that could provide strategic direction and education. One organizer, who was not in the ISO, said, ‘If the ISO was still around the movement would look different’.

Another organizer noted, ‘The PSM is suffering from not having a collective space to strategize, to talk about what are we doing, how are we getting there. We can’t just keep calling actions and expecting it to turn out different. They haven’t figured out a way to talk together. There are no summits, no regular coordinating meetings.’

In the absence of any such mechanisms, Jewish anti-Zionist groups ‘picked a lane’. JVP choose to engage in direct actions because they face fewer legal risks than Muslim or Palestinian activists. This is not to imply ISO would have been a silver bullet. On top of imploding in 2019, the ISO was often faulted by antiwar activists for sectarianism, and I have seen ISO cadre acting needlessly divisive in trying to ‘sharpen the line’.

Into this void stepped the Party for Socialism and Liberation. Two organizers said the PSL is allied with the Palestinian Youth Movement, which provides national leadership for Students for Justice in Palestine, and that the PSL also works closely with American Muslims for Palestine. The sources claim the PSL does not collaborate with left organizations outside its umbrella, hampering movement building. One headline-making Palestinian-led organization, the Brooklyn-based Within Our Lifetime (WOL), has been called a ‘one-woman show’. One organizer accurately described what I have also witnessed: ‘WOL doesn’t want to have any plan for an action. They throw themselves against the wall and the protest ends when the police attack.’ WOL marches are frequent and go on for hours. In late 2023, they attracted ten thousand youths, mainly Arab and Muslim. By the spring of 2024, it was hundreds, in part because they provided no legal support. A third organizer grimly described student organizing on some campuses. It matches my experience of OWS, Occupy ICE and the George Floyd Movement. They said:

Whoever says the most strident thing, is the most radical. A lot of it is super-performative. They don’t want to build alliances with faculty and staff. They’re the revolutionary agent and everyone else is a sellout. They are not open to a welcoming process where people may come in with a mix of ideas, good and bad, and engage in political education. It’s sectarian, it’s alienating, it’s juvenile.

In many ways, the moment was made for the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA). But the DSA was not made for this moment. The DSA has around 80,000 dues-paying members, but active members are far fewer. It is not a cadre organization, it is opposed to democratic centralism and it focuses mainly on electoral politics. One organizer said, ‘the DSA flubbed the George Floyd Movement, and then flubbed the Gaza movement’. Having a diffuse structure where chapters have considerable freedom to take positions and decide on campaigns has enabled productive organizing, particularly around labour. One DSA activist points out that its ‘internal life’ is complicated, with different caucuses ranging from Marxists on the left to social democrats on the right. The DSA could have expanded the PSM by mobilizing the white left and progressives, but its bureaucratic structure makes it very hard to move the entire organization into non-electoral work. The organizer claimed, ‘most of the people who are interested in building movements and building struggles have left the DSA’. Organization is the Achilles heel of the Palestine solidarity movement. There is a lack of national student leadership, a lack of overall national leadership and a lack of unifying Palestinian leadership in the Occupied Territories and worldwide.

Empires are defeated not only on the battlefield but primarily on the balance sheet. Israeli bonds have been downgraded multiple times, its economy is shrinking, and tens of thousands of well-educated young people who power its high-tech economy have fled abroad. Turkey, a major economic partner, has axed some trade with Israel, while activists have been staging sit-ins and blockades at Turkish ports targeting Israel-bound cargo ships. Colombia, Israel’s top supplier of coal, has stopped exports of the fuel that accounts for 20 per cent of Israel’s electricity supply. Belgium, Spain, Canada, the Netherlands, Italy and Britain have banned or restricted weapons sales. Foreign investors have dumped nearly $13 billion in Israeli stocks and bonds, and Israeli weapons makers were banned from or skipped trade shows. Pret A Manger dropped plans to open 40 stores; in a huge blow, Intel suspended work on a $25 billion chip plant; and Starbucks and McDonald’s admitted pro-Palestine boycotts against them have contributed to declining profits. Brutal regional powers don’t just disappear on their own, however. In the case of South Africa, the ANC marshalled wide support to guide an internal mass struggle that was largely nonviolent, a guerilla war with crucial support from the Cuban military and other revolutionary movements in Southern Africa, and an international solidarity movement that chipped away at the apartheid state economy through divestment and boycotts until the regime crumbled. At best, the PSM has only fragments of these components and Israel is far more integrated into the Western ruling order than South Africa ever was.

Israel’s genocide in Gaza serves the function of papering over a society at war with itself, between secular Jews and fanatical religious settlers, between Jews and second-class Israeli Arabs, between those who serve in the army and the poorly educated Orthodox who refuse to enlist. Foremost, Zionism has reached its historic conclusion as a genocidal racist ideology. There is no redeeming it, and modern states based in these ideas never last long.

I enjoyed the detailed mapping of movements (global justice, anti-war, occupy, PSM, etc.), but not much mention of anti-fossil fuel extraction and other environmental justice movements in West Virginia (MTR coal mining),Texas (KXL), North Dakota (DAPL), Minnesota (line 3), Virginia (mountain valley pipeline) and Atlanta (cop city). There was significant links and overlaps between those campaigns, and camps in terms of ideology, strategy, tactics and people. Seems like a missing piece. Why is that?

Hi Arun. May I republish this in the online version of Left Turn, the magazine I edit?